Martin Godsil was not a poetic man. With the exception of a book of dirty limericks on our family shelf, his taste in the "art of letters" was straightforward. On his first – and last – trip to the Seattle Reparatory Theatre he snored so loudly as to wake Falstaff from a dead drunken slumber. After that, literature was strictly the domain of women and his sensitive, overly-emotional, sickly asthmatic son. In summary, Dad was: Not-so-artsy. More into watching Monday Night Football, cowboy movies, and the occasional maudlin musical.

"Just look at that dancing, would ya - just look at that dancing! People don't dance like that at any more."

Nevertheless, when he named his last fiberglass Dragon Ariel, he knew exactly what he was doing. Joycean-style literary correspondences abound. Ariel was the faerie sprite who is bound to Prospero for one more spell before being released to freedom. Prospero was is the orchestrating Patriarch/Wizard on the desert isle and the closest analog to Shakespeare in all of his plays. In this instance of life imitating art, Prospero = Shakespeare = Martin Godsil, boat builder. As The Tempest was Shakespeare's last play, Ariel, US 288, would be Martin Godsil's very last fiberglass dragon, his last masterpiece.

And so once again Martin Godsil began to measure and cut and build; grind, design and refine. Project-life took on its normal focussed rhythm, a recurrent cycle of arriving home from work, greeting the family, changing into his paint-sweatshirt and chinos, mixing a drink and disappearing down into the workshop in the basement. The bandsaw whined, the drill press and grinder whirred. Every weekend he'd take the ferry to Bainbridge Island. He poured everything he'd learned over twenty years of sailing and boat building into one last racing machine. The goal: the 1983 Dragon World Championships, to be held right in our sailing backyard in Vancouver, Canada – just a three-hour drive Seattle. My dad knew English Bay like that back of his calloused, strongly-veined hands.

For the benefit of posterity, he documented the entire process in this photo album, which I found mouldering in my aunt's garage, amidst the shambles of old albums and old tarnished plaques and trophies that they'd loaded out during the pandemic. Along the spine it says "1982- 1983 Ariel." Here's a slideshow of the album, beginning with the cover:

"Just look at that dancing, would ya - just look at that dancing! People don't dance like that at any more."

Nevertheless, when he named his last fiberglass Dragon Ariel, he knew exactly what he was doing. Joycean-style literary correspondences abound. Ariel was the faerie sprite who is bound to Prospero for one more spell before being released to freedom. Prospero was is the orchestrating Patriarch/Wizard on the desert isle and the closest analog to Shakespeare in all of his plays. In this instance of life imitating art, Prospero = Shakespeare = Martin Godsil, boat builder. As The Tempest was Shakespeare's last play, Ariel, US 288, would be Martin Godsil's very last fiberglass dragon, his last masterpiece.

And so once again Martin Godsil began to measure and cut and build; grind, design and refine. Project-life took on its normal focussed rhythm, a recurrent cycle of arriving home from work, greeting the family, changing into his paint-sweatshirt and chinos, mixing a drink and disappearing down into the workshop in the basement. The bandsaw whined, the drill press and grinder whirred. Every weekend he'd take the ferry to Bainbridge Island. He poured everything he'd learned over twenty years of sailing and boat building into one last racing machine. The goal: the 1983 Dragon World Championships, to be held right in our sailing backyard in Vancouver, Canada – just a three-hour drive Seattle. My dad knew English Bay like that back of his calloused, strongly-veined hands.

For the benefit of posterity, he documented the entire process in this photo album, which I found mouldering in my aunt's garage, amidst the shambles of old albums and old tarnished plaques and trophies that they'd loaded out during the pandemic. Along the spine it says "1982- 1983 Ariel." Here's a slideshow of the album, beginning with the cover:

I tried various ways to organize these pictures, but settled on a slideshow. You can play the whole thing as a movie, watching the boat come to life, or slow down and read the captions where I've imparted what I know and recall of the process.

THE CHRISTENING

We join our christening in progress. The scene: the North End of Shilshole Bay Marina, the Dragon hanging in the air from the crane, a festive alphabet of nautical signal flags bedecking the stays fore and aft. Time: the Spring of 1982 (or 1983? I kind of feel like I was a sophomore). Hot battered rum for the gathered faithful.

Christening your boat brings good luck (unless it doesn’t) and guards a ship and it’s crew against the perils of the sea, icebergs, monsters of the deep and getting stuck on the wrong side of a wind shift. A princess or queen or another dignitary reads a passage or a prayer and invokes the protection of whatever Gods there are and then cracks a bottle of champagne across the yacht's nose. Above you can see my sister Dorothy Alice Godsil, ne Ambuske, christening Ariel.

Even before I found the above picture in this treasure of an album, I could see her clear as a bell in my minds eye, about 12 at the time, braces glinting in the cool late winter sunshine before she swings smashes the bottle across the nose of the boat.

So Ariel was officially ready. There was really only one question on the table: is it possible to craft, design, sculpt and otherwise train a crew like one builds a race boat to compete at the highest levels of international competition?

CREW-IN-TRAINING #1: THE FOREDECK

On foredeck, my father went with the relative unknown fresh out of Seattle Preparatory Academy, a young dinghy sailor with little to no big regatta experience. To be fair, he'd been grooming this particular prospect since birth. And over the years, this young sailor had been provided with everything he needed to succeed, and more. At the age of ten, he'd been given an El Toro, a ten foot pram for kids to learn to sail and race. He been given sailing lessons at Seattle Yacht Club, and later his own blue laser stored over by the boathouse at the University of Washington, He'd had opportunities to crew, and of course books – and long clinics over dinner where races were replayed and tactically dissected and rules rehashed.

And to be fair, there was a talented sailor hiding away in there somewhere, deep down beneath the whole teenage orange spiky hair rebellion shell. I was a teenager, normal in every respect, only more so. Prey to hormonal revolt, chronic defiance, incipient alcoholism, plus a tangle of mental health issues that the AMA would even diagnose for decades. I was a total shipwreck. A true Caliban. But my Dad's dream was to sail with his son, so my position at foredeck was a lock - a contract with a no-cut clause.

CREW-IN-TRAINING #2: THE TACTICIAN

And then there was Gary Powell. but I think my Dad believed that because Gary Powell worked at Microsoft and did some sort of brilliant nerdy stuff with computers that all you had to do was hand him a hand-held compass, and he would be a tactical genius in no time flat. Unfortunately, software engineering and sailboat racing are not transferable skills. Yes, there is logical analysis on a race course, but the data and variables are much more quantum than spreadsheet.

Just to riff a little: computers can drive a car. AI cannot race a sailboat. Computers have been kicking human ass at chess for decades, but computers can't win a sailboat race. Sailboat racing is game of presence and awareness; the ability to be absolutely focused on all things at once. You must use every sense. Your mind, your eyes, your proprioception, your balance, the feel of wind on your arm or cheek, the pull of the sheet on your hand, the touch of the helm – all of these elements comprise a meaningful and ever-changing flow of data. It's more jazz than math, more John Coltrane than Bertrand Russell – an alchemic mixture of the way the boat feels under you, your observed boat speed in relation to other boats, the shape of your sails, of theirs, your speed in relation to the shore; how your boat is moving through the water, how it feels beneath you and what that communicates. The wind on your skin, the touch of the tiller, the angle of the heel of the boat, the height, shape and direction of the waves of the waves and the direction and strength of the wind as it fills the sails, flicks the tell-tails and ripples the water with catspaws. It's said that the ancient Polynesian navigators could tell how far land was and in which direction just by which way their scrotum hung between their lThe algorithm got no ballsack. It's a little like that. You gotta use all of you, definitely.

THE CREW, IN SUMMARY

So instead of the more professional or at least experienced semi-pro crew he’d had in Travemünde – Pat Dore and David Jones – where he’d finished 5th against a really impressive and loaded fleet, my Dad had an incorrigible, toxic teenager and a sweet guy that could pull in the jib and tie a bowline but that was really the extent of his contribution to the 1983 Dragon Class World Championship campaign.

THE CAMPAIGN BEGINS

The drive to success was on. The training program would mean sailing in every single weekend regatta leading up to the 1983 Worlds which would be held in July. So drive we did. North from Seattle, up through Everett (which had a sawmill at the time) through Marysville and Mount Vernon through Bellingham past the Chuckanut drive turnoff that I always wanted to take just because of the name and then on to the border at Blaine “What’s the purpose of your visit?” “Sailing?” yep with a turn of the border guard's head he can see there's a big boat back there behind the Suburban and then a smile from the border guard who looked like your uncle Lloyd from Manitoba and a friendly wave-through, crossing into Canada and another 90 minutes or so to Vancouver and then surface streets to Royal Vancouver Yacht Club. So there was a lot of back-and-forth. A lot of practicing. Many night's spent at our friends' house on Point Grey Road. I remember all of it and none of it in particular. We made so many trips and it all blends together.

AND THEN WE SAIL INTO A HOLE

A hole is a windless place on the race course. Sometimes, through no fault of your own, you look up and all of a sudden the water near you is oil-slick flat. and the whole fleet seems to sail right around you. Off in the distance you can see the water dimpled and rippling with wind ,while you you're stuck, slogging and powerless to move. This is where our story sails into a narrative hole. Stuck in an emotional slough; the winds of inspiration momentarily stilled. I have only the vaguest of memories of what happened on the race course that summer. Our performance was solidly middle of the fleet, slightly better than the bunched up regular sailor joes in the middle of the, just-glad-to-be-there main part of the feel, while failing to crack the upper echelon.

THE FEW THINGS I DO REMEMBER

Memory #1. I remember walking down onto the dock on the morning of the first race feeling the excitement and hope in the air and feeling all puffed up and having all this intensity as if I could will myself to victory over these more experienced and seasoned sailors. And then getting a dose of reality once we got out there.

Memory #2. Every morning, there was a a six-pack of Heineken cans on the boat every morning and free posters emblazoned with the Du Maurier cigarette logo. Yep, the 1983 World Championships were sponsored by a beer company and a cigarette company. And I remember going back to the house after the racing and sitting on the couch and looking out across English Bay and "taking the edge off" by chain smoking an entire pack of Du Maurier cigarettes. I remember Mary Clasby walking in and observing the air blue with smoke , and then saying “Tough sailing with your dad, huh?” I remember her kindness and compassion and thinking she probably wouldn’t tell my parents I was smoking.

Memory #3. There was a Dutch girl, my age. Blond, with a warm smile. She and her brother crewed for their Dad – NL 214 - I have no idea why I remember their sail number, but it made an impression. I had a crush on her and thought since were the same age, we could be friends. Unfortunately there was a handsome slightly older bloke from New Zealand who outclassed me on every front. I remember with absolute clarity this macho Kiwi tearing off his shirt and jumping in the water and swimming over to the dutch girl's boat, muscular arms thrashing the water, and then pulling himself up onto the boat, tanned abs glistening tight and wet from the saltwater. To my horror, he had her giggling and laughing and covering her face with one accented joke after another. But I didn’t give up. I remember asking her to dance at a club after the race. About a minute in, I realized I’d made the worst decision of my young life. Cement filled in my shoes and my pants felt like I'd dropped a load. I stepped awkwardly from side to side, vaguely approximating the beat of whatever crappy ‘Stars on 45” type track was playing. Her eyes looked over my shoulder and around the room. When the song finished I crawled under my rock, a beaten little Pacific Northwest hermit crab.

Memory #4. I don't remember if this particularly memory was this regatta or another regatta, but I remember being on starboard tack so we technically had the right of way and my Dad T-boning a gray dragon owned by Rick Hermes and helmed in this particular regatta by Tech Jones. I remember quite clearly how our bow ran up over the gunnel of the other dragon and like Robin Hood's arrow splitting another arrrow as it seeks the bulls' eye, piercing the aluminum mast of the other dragon, which folded over, dunking the sails and everything into the water. I was momentarily paralyzed; slack-jawed and powerless to move. I remember Rick Hermes - a super nice guy and owner of the boat running up to the mast as if he was going to catch the sails before they dunked in the water. For a sensitive little sprite like me, I might have well have been watching the Lusitania go down. But my father didn't miss a beat – started yelling to get the sails in and start the race. That shocked me from my reverie. I have no doubt that this was a aggressive, move on my Dad's part and aimed at Tech Jones, the helms person, who was famously an uptight screamer and pathologically aggressive sailor in his own right.

I was busy maneuvering the sails and did not see the boat until the last minute. In hindsight, I am both horrified and in awe of my father's ability to compartmentalize and simply move on. Could he have made a better effort to avoid a collision and at least made it more of a glancing blow? Maybe. I was shocked and amazing that there was no blowback back on shore. No one said a damn thing back at the club.

Memory #5. And finally, at a post-race get-together one of the Australian speaking in dark grumbling tones how utterly unfair the course was. I do remember that. And that's is he real reason I don't remember any specific race too well. Because every race was a carbon copy of the last. "A fucking one-way street,” as an Aussie so succinctly expressed it, and took a big swig of Kokanee, as if to rinse away the bitterness.

A F%&!!ING ONE-WAY STREET

Sailing with the Vancouver skyline as a backdrop is as beautiful as sailing in a postcard. But in the summer, with the prevailing on-shore westerly blowing in from the Straight of Georgia, the locals know – and the world would soon find out – the game is rigged. panish Banks and then short-tack up the shore, all the while trying to stay out in the current. Anyone who goes out into the middle of the bay will find themselves far behind, no matter how the wind looks. If you’re in dirty air at the start, there's no way to tack out and make up time later. Because in the words of the Australian, "it's an effing one way street." There is no way around this. It’s as inevitable as gravity. All of the normal rules of sailboat racing acumen don’t apply. So the people that have sailed in Vancouver all of their lives have an advantage.

How it would generally go on our boat: We stuck in bad air at the start, and we need to tack. I’m rolling my eyes but my Dad insists. How did we get here again? Another sub-par start. Nothing in life is as frustrating as being below and ½ a boat length behind the leader with the best start on a course you know is a one way street, because you know that even though you could literally almost reach out and touch their boom if they let go of the mainsheet that you will slowly, inevitably fall back and back and back. Your captain will begin insisting you tack and in your sharp adolescent brain you’ll think – why? You tack out you’re screwed. You stay where you are you’re screwed. You could try to go lower and just increase your speed if you could get out of their wind shadow – called footing. But at the core of it all is that sinking feeling, you’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if don’t. You’ll never been in clear air. You’ve already broken rule of of sailboat racing, according to Marty Godsil. “Get ahead and stay ahead.” We would start towards the lee end of the line on starboard tack with Bob Burgess the eventual winner nearly always getting the pole position. The gun would go off and the drag race to get out of the tide would begin. The first boat to reach the reverse current happening along the shore would be lifted above all of the others, and everyone would fall in line. And once you’re ahead, rule #2 of sailboat racing kicks in. Cover the competition. And if you’re smart and conservative, there’s pretty much no way any other boat could get in front of you, because they must sail through the disturbed bad air of your wind shadow.

To tack out of bad air and into the greater contrary current happening in the middle of the boat was basically a death sentence to your dreams of placing in the top of the fleet, but this is what my father would inevitably do. And so every race where were mired in bad air, that makes every decision a Hobson’s choice of lesser evils.

AND THE WINNER IS

In the end, one of my Dad's boats did win. My dad’s Canadian nemesis, the Alpha-Dog of the Vancouver fleet, Bob Burgess, won the World Championships sailing Mistral, KA 118. You'll remember Mistral, US 250, as the yellow boat, clear as sunlight, the beautiful Borresen-built wooden dragon with the teak decks that he had campaigned for the 1972 Olympic games. Ironic? Perhaps.

I have a shadowy recollection of Bob Burgess lead growing. - as sense of being trapped, falling farther and farther behind, like in a nightmare when you're running from something and you can never go fast enough except in this case, you're doing the chasing and the leaders are receding like hope farther and farther into the distance - there's the very-mortal Bob Burgess who we are used to racing against, chased by a few eli. One must give him credit, though; even after everyone figured out the nature of the race, he was still able to master the start, master the drag race to the beach, and stay at or near the top for the remainder of the regatta.

For his part, my dad always took his lumps without bitterness; victory and defeat with equanimity. He could be an absolute maniac on the water, but once the race was over, he was always appreciative of the experience of being on the water, and to his crew. “That was so fun.” And I would think ... "fun?" But I always did take thing too seriously. My Dad could have done better with a better crew. But this was the sacrifice he made to sail with his son. He deserved a better result on the racecourse, considering how much he'd put into the boat, but some things are more important than success. Loyalty and family for one. And for me, it was all part of growing up and getting a front row seat to see a truly original, imperfect, extraordinary human being doing what he loves.

CODA

Max Godsil ended up straightening out, but it took a little while. Stay tuned.

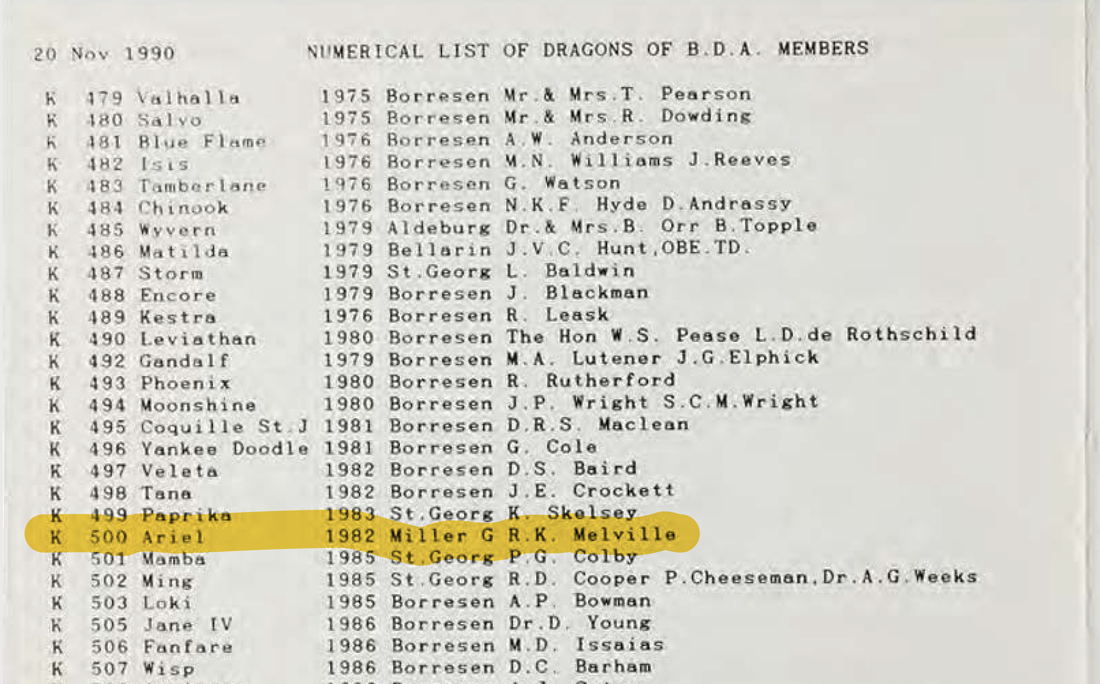

Ariel went to Burnham on Crouch, UK to become K500. Ironic that when I looked up the British Yacht Registry, Ariel is registered as a "Miller." But we know who really built her. We have the proof, documented, here.

We join our christening in progress. The scene: the North End of Shilshole Bay Marina, the Dragon hanging in the air from the crane, a festive alphabet of nautical signal flags bedecking the stays fore and aft. Time: the Spring of 1982 (or 1983? I kind of feel like I was a sophomore). Hot battered rum for the gathered faithful.

Christening your boat brings good luck (unless it doesn’t) and guards a ship and it’s crew against the perils of the sea, icebergs, monsters of the deep and getting stuck on the wrong side of a wind shift. A princess or queen or another dignitary reads a passage or a prayer and invokes the protection of whatever Gods there are and then cracks a bottle of champagne across the yacht's nose. Above you can see my sister Dorothy Alice Godsil, ne Ambuske, christening Ariel.

Even before I found the above picture in this treasure of an album, I could see her clear as a bell in my minds eye, about 12 at the time, braces glinting in the cool late winter sunshine before she swings smashes the bottle across the nose of the boat.

So Ariel was officially ready. There was really only one question on the table: is it possible to craft, design, sculpt and otherwise train a crew like one builds a race boat to compete at the highest levels of international competition?

CREW-IN-TRAINING #1: THE FOREDECK

On foredeck, my father went with the relative unknown fresh out of Seattle Preparatory Academy, a young dinghy sailor with little to no big regatta experience. To be fair, he'd been grooming this particular prospect since birth. And over the years, this young sailor had been provided with everything he needed to succeed, and more. At the age of ten, he'd been given an El Toro, a ten foot pram for kids to learn to sail and race. He been given sailing lessons at Seattle Yacht Club, and later his own blue laser stored over by the boathouse at the University of Washington, He'd had opportunities to crew, and of course books – and long clinics over dinner where races were replayed and tactically dissected and rules rehashed.

And to be fair, there was a talented sailor hiding away in there somewhere, deep down beneath the whole teenage orange spiky hair rebellion shell. I was a teenager, normal in every respect, only more so. Prey to hormonal revolt, chronic defiance, incipient alcoholism, plus a tangle of mental health issues that the AMA would even diagnose for decades. I was a total shipwreck. A true Caliban. But my Dad's dream was to sail with his son, so my position at foredeck was a lock - a contract with a no-cut clause.

CREW-IN-TRAINING #2: THE TACTICIAN

And then there was Gary Powell. but I think my Dad believed that because Gary Powell worked at Microsoft and did some sort of brilliant nerdy stuff with computers that all you had to do was hand him a hand-held compass, and he would be a tactical genius in no time flat. Unfortunately, software engineering and sailboat racing are not transferable skills. Yes, there is logical analysis on a race course, but the data and variables are much more quantum than spreadsheet.

Just to riff a little: computers can drive a car. AI cannot race a sailboat. Computers have been kicking human ass at chess for decades, but computers can't win a sailboat race. Sailboat racing is game of presence and awareness; the ability to be absolutely focused on all things at once. You must use every sense. Your mind, your eyes, your proprioception, your balance, the feel of wind on your arm or cheek, the pull of the sheet on your hand, the touch of the helm – all of these elements comprise a meaningful and ever-changing flow of data. It's more jazz than math, more John Coltrane than Bertrand Russell – an alchemic mixture of the way the boat feels under you, your observed boat speed in relation to other boats, the shape of your sails, of theirs, your speed in relation to the shore; how your boat is moving through the water, how it feels beneath you and what that communicates. The wind on your skin, the touch of the tiller, the angle of the heel of the boat, the height, shape and direction of the waves of the waves and the direction and strength of the wind as it fills the sails, flicks the tell-tails and ripples the water with catspaws. It's said that the ancient Polynesian navigators could tell how far land was and in which direction just by which way their scrotum hung between their lThe algorithm got no ballsack. It's a little like that. You gotta use all of you, definitely.

THE CREW, IN SUMMARY

So instead of the more professional or at least experienced semi-pro crew he’d had in Travemünde – Pat Dore and David Jones – where he’d finished 5th against a really impressive and loaded fleet, my Dad had an incorrigible, toxic teenager and a sweet guy that could pull in the jib and tie a bowline but that was really the extent of his contribution to the 1983 Dragon Class World Championship campaign.

THE CAMPAIGN BEGINS

The drive to success was on. The training program would mean sailing in every single weekend regatta leading up to the 1983 Worlds which would be held in July. So drive we did. North from Seattle, up through Everett (which had a sawmill at the time) through Marysville and Mount Vernon through Bellingham past the Chuckanut drive turnoff that I always wanted to take just because of the name and then on to the border at Blaine “What’s the purpose of your visit?” “Sailing?” yep with a turn of the border guard's head he can see there's a big boat back there behind the Suburban and then a smile from the border guard who looked like your uncle Lloyd from Manitoba and a friendly wave-through, crossing into Canada and another 90 minutes or so to Vancouver and then surface streets to Royal Vancouver Yacht Club. So there was a lot of back-and-forth. A lot of practicing. Many night's spent at our friends' house on Point Grey Road. I remember all of it and none of it in particular. We made so many trips and it all blends together.

AND THEN WE SAIL INTO A HOLE

A hole is a windless place on the race course. Sometimes, through no fault of your own, you look up and all of a sudden the water near you is oil-slick flat. and the whole fleet seems to sail right around you. Off in the distance you can see the water dimpled and rippling with wind ,while you you're stuck, slogging and powerless to move. This is where our story sails into a narrative hole. Stuck in an emotional slough; the winds of inspiration momentarily stilled. I have only the vaguest of memories of what happened on the race course that summer. Our performance was solidly middle of the fleet, slightly better than the bunched up regular sailor joes in the middle of the, just-glad-to-be-there main part of the feel, while failing to crack the upper echelon.

THE FEW THINGS I DO REMEMBER

Memory #1. I remember walking down onto the dock on the morning of the first race feeling the excitement and hope in the air and feeling all puffed up and having all this intensity as if I could will myself to victory over these more experienced and seasoned sailors. And then getting a dose of reality once we got out there.

Memory #2. Every morning, there was a a six-pack of Heineken cans on the boat every morning and free posters emblazoned with the Du Maurier cigarette logo. Yep, the 1983 World Championships were sponsored by a beer company and a cigarette company. And I remember going back to the house after the racing and sitting on the couch and looking out across English Bay and "taking the edge off" by chain smoking an entire pack of Du Maurier cigarettes. I remember Mary Clasby walking in and observing the air blue with smoke , and then saying “Tough sailing with your dad, huh?” I remember her kindness and compassion and thinking she probably wouldn’t tell my parents I was smoking.

Memory #3. There was a Dutch girl, my age. Blond, with a warm smile. She and her brother crewed for their Dad – NL 214 - I have no idea why I remember their sail number, but it made an impression. I had a crush on her and thought since were the same age, we could be friends. Unfortunately there was a handsome slightly older bloke from New Zealand who outclassed me on every front. I remember with absolute clarity this macho Kiwi tearing off his shirt and jumping in the water and swimming over to the dutch girl's boat, muscular arms thrashing the water, and then pulling himself up onto the boat, tanned abs glistening tight and wet from the saltwater. To my horror, he had her giggling and laughing and covering her face with one accented joke after another. But I didn’t give up. I remember asking her to dance at a club after the race. About a minute in, I realized I’d made the worst decision of my young life. Cement filled in my shoes and my pants felt like I'd dropped a load. I stepped awkwardly from side to side, vaguely approximating the beat of whatever crappy ‘Stars on 45” type track was playing. Her eyes looked over my shoulder and around the room. When the song finished I crawled under my rock, a beaten little Pacific Northwest hermit crab.

Memory #4. I don't remember if this particularly memory was this regatta or another regatta, but I remember being on starboard tack so we technically had the right of way and my Dad T-boning a gray dragon owned by Rick Hermes and helmed in this particular regatta by Tech Jones. I remember quite clearly how our bow ran up over the gunnel of the other dragon and like Robin Hood's arrow splitting another arrrow as it seeks the bulls' eye, piercing the aluminum mast of the other dragon, which folded over, dunking the sails and everything into the water. I was momentarily paralyzed; slack-jawed and powerless to move. I remember Rick Hermes - a super nice guy and owner of the boat running up to the mast as if he was going to catch the sails before they dunked in the water. For a sensitive little sprite like me, I might have well have been watching the Lusitania go down. But my father didn't miss a beat – started yelling to get the sails in and start the race. That shocked me from my reverie. I have no doubt that this was a aggressive, move on my Dad's part and aimed at Tech Jones, the helms person, who was famously an uptight screamer and pathologically aggressive sailor in his own right.

I was busy maneuvering the sails and did not see the boat until the last minute. In hindsight, I am both horrified and in awe of my father's ability to compartmentalize and simply move on. Could he have made a better effort to avoid a collision and at least made it more of a glancing blow? Maybe. I was shocked and amazing that there was no blowback back on shore. No one said a damn thing back at the club.

Memory #5. And finally, at a post-race get-together one of the Australian speaking in dark grumbling tones how utterly unfair the course was. I do remember that. And that's is he real reason I don't remember any specific race too well. Because every race was a carbon copy of the last. "A fucking one-way street,” as an Aussie so succinctly expressed it, and took a big swig of Kokanee, as if to rinse away the bitterness.

A F%&!!ING ONE-WAY STREET

Sailing with the Vancouver skyline as a backdrop is as beautiful as sailing in a postcard. But in the summer, with the prevailing on-shore westerly blowing in from the Straight of Georgia, the locals know – and the world would soon find out – the game is rigged. panish Banks and then short-tack up the shore, all the while trying to stay out in the current. Anyone who goes out into the middle of the bay will find themselves far behind, no matter how the wind looks. If you’re in dirty air at the start, there's no way to tack out and make up time later. Because in the words of the Australian, "it's an effing one way street." There is no way around this. It’s as inevitable as gravity. All of the normal rules of sailboat racing acumen don’t apply. So the people that have sailed in Vancouver all of their lives have an advantage.

How it would generally go on our boat: We stuck in bad air at the start, and we need to tack. I’m rolling my eyes but my Dad insists. How did we get here again? Another sub-par start. Nothing in life is as frustrating as being below and ½ a boat length behind the leader with the best start on a course you know is a one way street, because you know that even though you could literally almost reach out and touch their boom if they let go of the mainsheet that you will slowly, inevitably fall back and back and back. Your captain will begin insisting you tack and in your sharp adolescent brain you’ll think – why? You tack out you’re screwed. You stay where you are you’re screwed. You could try to go lower and just increase your speed if you could get out of their wind shadow – called footing. But at the core of it all is that sinking feeling, you’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if don’t. You’ll never been in clear air. You’ve already broken rule of of sailboat racing, according to Marty Godsil. “Get ahead and stay ahead.” We would start towards the lee end of the line on starboard tack with Bob Burgess the eventual winner nearly always getting the pole position. The gun would go off and the drag race to get out of the tide would begin. The first boat to reach the reverse current happening along the shore would be lifted above all of the others, and everyone would fall in line. And once you’re ahead, rule #2 of sailboat racing kicks in. Cover the competition. And if you’re smart and conservative, there’s pretty much no way any other boat could get in front of you, because they must sail through the disturbed bad air of your wind shadow.

To tack out of bad air and into the greater contrary current happening in the middle of the boat was basically a death sentence to your dreams of placing in the top of the fleet, but this is what my father would inevitably do. And so every race where were mired in bad air, that makes every decision a Hobson’s choice of lesser evils.

AND THE WINNER IS

In the end, one of my Dad's boats did win. My dad’s Canadian nemesis, the Alpha-Dog of the Vancouver fleet, Bob Burgess, won the World Championships sailing Mistral, KA 118. You'll remember Mistral, US 250, as the yellow boat, clear as sunlight, the beautiful Borresen-built wooden dragon with the teak decks that he had campaigned for the 1972 Olympic games. Ironic? Perhaps.

I have a shadowy recollection of Bob Burgess lead growing. - as sense of being trapped, falling farther and farther behind, like in a nightmare when you're running from something and you can never go fast enough except in this case, you're doing the chasing and the leaders are receding like hope farther and farther into the distance - there's the very-mortal Bob Burgess who we are used to racing against, chased by a few eli. One must give him credit, though; even after everyone figured out the nature of the race, he was still able to master the start, master the drag race to the beach, and stay at or near the top for the remainder of the regatta.

For his part, my dad always took his lumps without bitterness; victory and defeat with equanimity. He could be an absolute maniac on the water, but once the race was over, he was always appreciative of the experience of being on the water, and to his crew. “That was so fun.” And I would think ... "fun?" But I always did take thing too seriously. My Dad could have done better with a better crew. But this was the sacrifice he made to sail with his son. He deserved a better result on the racecourse, considering how much he'd put into the boat, but some things are more important than success. Loyalty and family for one. And for me, it was all part of growing up and getting a front row seat to see a truly original, imperfect, extraordinary human being doing what he loves.

CODA

Max Godsil ended up straightening out, but it took a little while. Stay tuned.

Ariel went to Burnham on Crouch, UK to become K500. Ironic that when I looked up the British Yacht Registry, Ariel is registered as a "Miller." But we know who really built her. We have the proof, documented, here.

AND WE SAIL INTO THE SUNSET

If Shakespeare rode further west. Past the shipwreck shores and jungle wilderness filled with island savages. Waved his wandlike pen across a continent, crossing plains, fording rivers, traversing mountains, out somewhere west of Laramie. If Shakespeare wrote a cowboy movie. Would it be the story of a Rancher who passes on and haunts his former ranch, his brilliant yet ineffective son stuck in a spider web of his own indecision and paranoid neuroisis … or perhaps, memory failing with age, he generously divides his ample ranchland among three daughters, and, misjudging loyalties, finds himself out on his ass. Would the neighboring faerie folk in them thar hills might perchance lay a spell of a dream on the townsfolk and three cowboys take a vow of chastity and then or else the son and daughter of two rival families, one native, one settler ... how about let's call it the Kwakuitl and the McCoys. Open mid-skirmish, cowboys and indian braves trading blows. Couple scenes later … daughter of the Patriarch falls for the handsome young Indian brave who kidnaps her and treats her kindly and shows her how listen to the voices upon the wind, and the lessons hidden under leaf and rock. Years later, a mother, older and wiser a savage only in dress, she is recaptured by the white people who mistake her for an Indian princess. If Shakespeare wrote a cowboy movie, would it be a history or a tragedy or a comedy? A yet to be invented genre of play. We are all players, and all we know for certain is that memory is deep and uncharted and our lives sink slowly below it’s cold gray surface and sink into near-limitless depths while lidless eyes watch as our own bioluminescence grows fainter and fainter as we fade ever lower into the cold and dark and like the last moment of a sunset before it in winks out, we are all writing on water.

If Shakespeare rode further west. Past the shipwreck shores and jungle wilderness filled with island savages. Waved his wandlike pen across a continent, crossing plains, fording rivers, traversing mountains, out somewhere west of Laramie. If Shakespeare wrote a cowboy movie. Would it be the story of a Rancher who passes on and haunts his former ranch, his brilliant yet ineffective son stuck in a spider web of his own indecision and paranoid neuroisis … or perhaps, memory failing with age, he generously divides his ample ranchland among three daughters, and, misjudging loyalties, finds himself out on his ass. Would the neighboring faerie folk in them thar hills might perchance lay a spell of a dream on the townsfolk and three cowboys take a vow of chastity and then or else the son and daughter of two rival families, one native, one settler ... how about let's call it the Kwakuitl and the McCoys. Open mid-skirmish, cowboys and indian braves trading blows. Couple scenes later … daughter of the Patriarch falls for the handsome young Indian brave who kidnaps her and treats her kindly and shows her how listen to the voices upon the wind, and the lessons hidden under leaf and rock. Years later, a mother, older and wiser a savage only in dress, she is recaptured by the white people who mistake her for an Indian princess. If Shakespeare wrote a cowboy movie, would it be a history or a tragedy or a comedy? A yet to be invented genre of play. We are all players, and all we know for certain is that memory is deep and uncharted and our lives sink slowly below it’s cold gray surface and sink into near-limitless depths while lidless eyes watch as our own bioluminescence grows fainter and fainter as we fade ever lower into the cold and dark and like the last moment of a sunset before it in winks out, we are all writing on water.